Spectres in Change. Fieldnotes #2

Posted Dec. 10, 2019 by Nik Gaffney and Maja KuzmanovićSeili* 2019-05-14 to 2019-05-26

How to land in a place is a perpetual question for those of us who live and work nomadically or trans-locally. The fleeting moment of landing can be easily missed on your way somewhere. Whether you step off a boat, cross the threshold of someone's home, or start a new collaboration. Yet how you land matters. It acknowledges that the place in which you've landed has an agency of its own and a history that you have been apart from. Landing could be seen as a ritual beginning with a place and those who call it home.

In 2017 we founded FoAM Earth as a nomadic studio within the FoAM network. We were in the process of uprooting ourselves to begin a multi-year drift when we met Taru Elfving. She was moving back to her native Finland and keen to collaborate with artists capable of weaving together "otherwise incompatible perspectives and positions, while drawing out points of friction and leakage between different epistemologies, across micro and macro, or local and planetary scales." A few months later we joined a group of such artists and curators for the initiation of Spectres in Change on the island of Seili. Relationships were forged and conversations continued. All of us expressed an interest in returning to the island, to actively engage, as researchers, resident artists, or other roles as appropriate. So when Taru invited us to a second Spectres retreat on Seili, we were keen to combine it with a short research residency.

The retreat was focused on different practices of landing. The focus encouraged us to reflect on how we approach new places and unfamiliar contexts when working nomadically. For us landing includes listening and observing, sensing and attuning, sharing stories and experiences. Getting to know a place, however briefly and incompletely. What follows is a meander through some of our landing practices, entwined with the fieldnotes from our time on Seili during May 2019.

Arrival

Helsinki, Turku, Nauvo/Nagu. A long dazed journey by train, bus and boat brought us to the island of Seili. Late afternoon. Dinner was ready. Taru Elfving, our hostess and curator, invited us to temporarily remove ourselves from our daily pressures and to commit to a working retreat in the Archipelago Research Institute. A time and place to ask questions and explore responses to the environmental challenges and complex histories of the island. During the retreat we would look at these issues through the lens of "landing" — the condition of arriving and departing as guests on the island and within a scientific community. To explore the different approaches, meanings and methods people use to "land".

Storytelling

"There are experiences of landscape that will always resist articulation, and of which words offer only a remote echo – or to which silence is by far the best response. Nature does not name itself. Granite does not self-identify as igneous. Light has no grammar. Language is always late for its subject. (...) But we are and always have been name-callers, christeners. Words are grained into our landscapes, and landscapes grained into our words. ‘Every language is an old-growth forest of the mind,’ in Wade Davis’s memorable phrase. We see in words: in webs of words, wefts of words, woods of words. The roots of individual words reach out and intermesh, their stems lean and criss-cross, and their outgrowths branch and clasp." —Robert Macfarlane, Landmarks

Words, especially when intertwined into stories are an age-old "landing" technology. They allow you to get to know a place guided by your human hosts. Through stories shaped by the land they inhabit. A subjective reading of the landscape, filtered through the local culture, history and personal experience. Storytelling can connect the fleeting moment of landing to the deeper temporal layers of a place.

Ilppo welcomed us to Seili with a guided walk — a form of situated storytelling perfectly suited for welcoming new arrivals to the island. His personal story as a researcher on and around the island covers several decades. His family's ties to the Turku Archipelago span generations. He is at home here even though he doesn't live on the island. He leaves often, but keeps returning in a pattern of intermittent yet perpetual landings.

We gather in front of the church, meander through the old graveyard and walk past a scattering of buildings amidst the groves of deciduous trees. We have been on this walk before, two years ago. In a similar retreat with different people. The familiar stories of exclusion, leprosy, religion, community, geopolitics and mental illness are filled in with new details.

The "new" wooden church was built during a short summer in 1733, and still remains standing. A small bench by the altar is the only remnant of the first church that was neglected and eventually demolished in the early 1700s. At the entrance to the church we stop by the well worn stairs. Stairs for the "unclean" post-partum women, to prevent them from defiling of the inner sanctum, yet allow them to attend the church services. The cemetery behind the church is just as eerie as we remembered it, with mainly female names on fading gravestones. Most of them were patients in the mental asylum. Some were truly ill, others might have been "hysterical" or otherwise inconvenient. Sent to the island to live and die isolated from society. Alongside the patients are the graves of the hospital staff, including several generations of the Holländer family.

The island has been inhabited since the middle ages. It became a leper colony in 1619. The island now known as Seili was two distinct islands as recently as 400 years ago. One island was home for the sick, the other for the staff and clergy. Gradually, at a rate of around 5mm per year (and ever so slightly faster further north along the coast) the land rose above the sea and even now continues it's slow rise. The land masses in the Archipelago sea have been rising this way since the last ice age. The process is known as "post glacial rebound". The Earth stretching out, expanding after the long compression of massive ice sheets. Although the island moves upwards, it has remained more or less in the same place. While it's currently considered part of Finland, at other times in history it has been considered part of Sweden and Russia. It has gone from being an isolated hospital to becoming a research institute in the 1960s, and more recently a tourist destination.

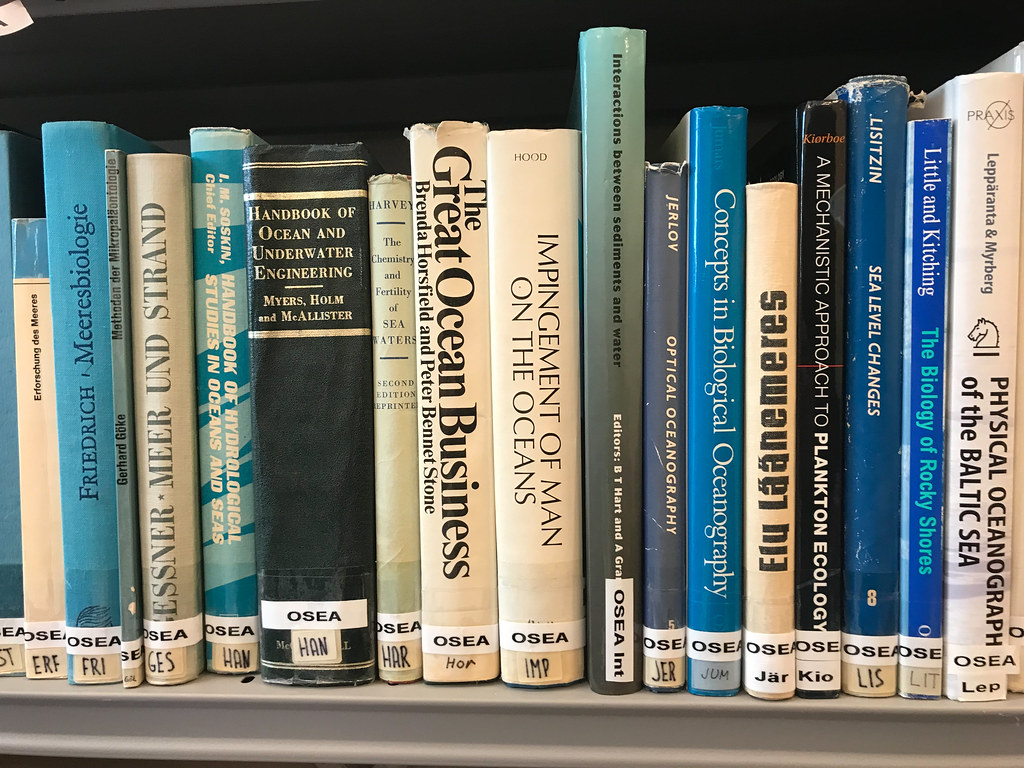

We explored the former hospital laundry, repurposed as a scientific library and microscopy lab. We spotted ancient tags carved into the wood and rock across the island co-existing with framed hospital records and scientific posters expounding new research findings. Only a few historical documents are still on the island. Most of the materials have been taken to Turku, or are scattered through Swedish and Russian archives. On the island itself the history echoes in guided tours during the summer tourist season.

We ended our walk at the research institute, in what was once the main hospital building. Our presence is overlaid with memories and moments of déjà vu, reminders of our last visit to the island. Colder this time, quieter. Early spring rather than midsummer.

Observation

Observation as an approach to "landing" is common in both arts and sciences. "Observe and interact" is also the first permaculture principle — "By taking the time to engage with nature we can design solutions that suit our particular situation". When landing in an unfamiliar place (or returning to a place that used to be familiar), observe the place to understand before interfering. You might find yourself driven by survival instincts, surveying potential threats, or maybe you feel moved by a humility and respect for the land and people you're about to engage with. Observing acknowledges an initial distance between yourself and the place you're landing in.

Jasmin and Johannes invited us into their work, through the process of scientific observation. Well established methods coexisted alongside emerging research. Time series carefully collected over decades. Metabarcoding of plankton (mostly) DNA. We descended into complex relationships within changing environments illustrated by the lives, diets and illnesses of animals, plants and plankton in the Baltic sea.

Sometimes, the act of observation detaches the observer from the observed. yet it can also bring the observer and observed even closer. Some forms of observation demand rather invasive procedures. As Johannes cut open recently frozen herring bellies in search of small white worms, he told us of parasites, changes in habitat, shifting populations, rising water temperature. Johannes deftly picked the herring brain, dug out each of its otoliths, then discarded the carcass. The data had been collected. The fish specimens used in their research have all been caught by the scientists themselves. Johannes is the son of a fisherman. The tacit skills of making nets and catching fish have been passed on from father to son, albeit in service of another field. There are no commercial fishermen able to provide the herring required for ongoing research any longer, as nets and lines have been abandoned for commercial trawling. Fishing mostly happens elsewhere now. Scientific research has unintentionally, yet quite willingly, facilitated a particular conservation of cultural heritage.

One of the long running research projects on Seili is based on observing the spread of tick populations across the region. Data collection started in the 1960s. At regular intervals the scientists count, collect and analyse ticks, noting their location, habitat and stage of life. Alongside several environmental variables, such as temperature and humidity a more detailed story emerges. To contribute to the time series, we collected ticks using a white sheet (1m square), tweezers and alcohol. Ideally, a time series requires methods and tools to remain consistent throughout the collection. The consistency and continuity help reduce variables, minimising complications over extended periods of time as changing groups of researchers add their observations. Each scientist adds to the sequence, with a handful, or hundreds, or perhaps thousands of samples. The tools used for data collection at the institute range from the latest DNA handling tech to a well used assemblages of buckets, funnels, tape and rope. Whatever is around can become a tool for scientific observation. Green jacket biology alongside the biology of white lab coats.

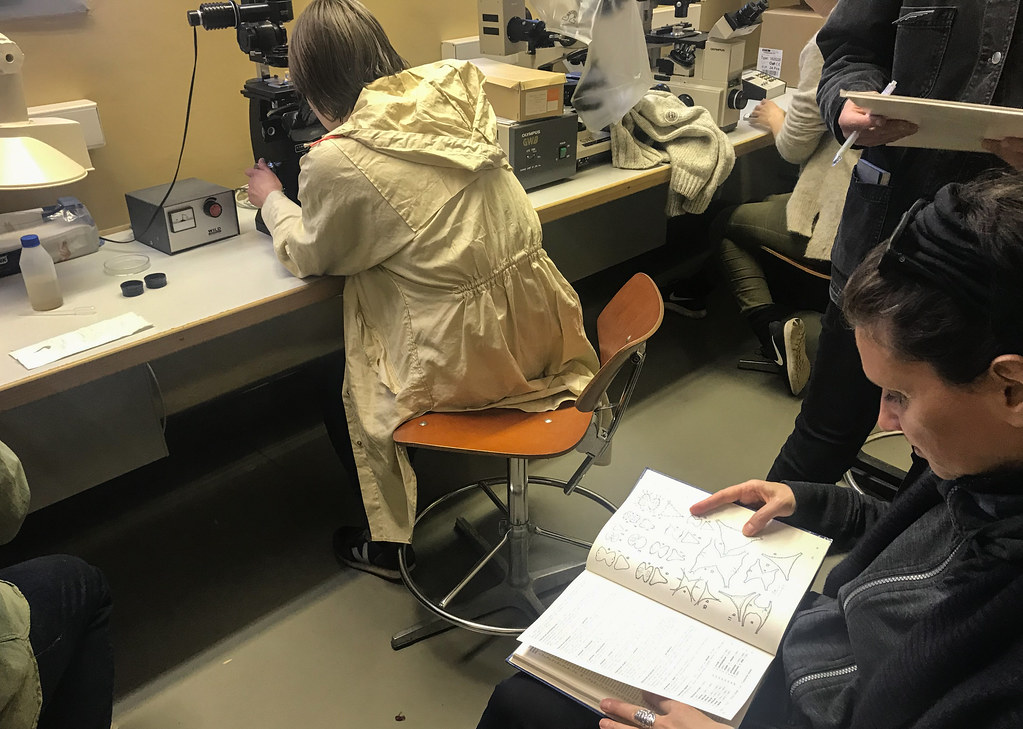

During a microscopy session we observed life at smaller-than-human scales. Mostly plankton and ticks (with the occasional fingernail, food fragment or phone screen "for reference"). Beauty and the beasts. Ticks in various stages of life. Each stage initiated by drinking blood. We discover that ticks don't "eat" blood. It's used more like a raw material to build their carapace, so their opacity tends to increase with age. After becoming acquainted with monstruously magnified ticks, we increased the magnification. We could now observe plankton. Assisted by a few plankton identification guides and an antique plankton counter we watched the layers of beings adrift or flickering. Translucent globules and fairy-like shrimp. Still life with the occasional ricochet ocurring at a microscopic scale. By the end of the session our eyes hurt, we had trouble focusing, yet our minds remained full of curious shapes and gravity-defying movements.

Sharing

Landing in a place inhabited by humans usually involve some form of sharing. Getting to know each other through formal or informal rituals of introduction, by sharing food and drinks, exchanging gifts and experiences. Landing in a different culture or institutional context can require a certain amount of negotiation and adaptation. Sharing knowledge and practices, protocols and daily rhythms can help identify potential common ground, as well as things that might be divergent or complementary.

The wall-filling map of the archipelago reveals a complex geology and cultural geography of the region. Thousands of islands and hundreds of years of human habitation. The open landscape of characteristically biodiverse meadows has been shaped by centuries of grazing cattle and small scale agriculture. Katja from the Archipelago Sea Biosphere Reserve joined us for an afternoon, to share her work with organisations in the archipelago such as small farmers and businesses running transport infrastructure. The Biosphere Reserve encourages human activities that can co-exist in mutually beneficial relationships with the ecosystem of the Archipelago. They support reducing food waste and plastic pollution, for example, while increasing the quality of environmental and cultural tourism. A young chef on Korpo joined the Biosphere Reserve specifically to design recipes in response to environmental challenges in the region. What does climate change in the Archipelago taste like?

Some of us shared our experiences as artists "landing" in scientific contexts. Helena and Mark from Matterlurgy found that arriving in a scientific lab always requires an initial period of observing, questioning and conversing. The hesitant dance of collaboration in unfamiliar contexts. When engaging with scientists, they found common ground in improvisation, with being curious about each other's tools and instruments. They talked about their experience with "Rehearsing for Uncertain Futures", a collaboration with the Earth scientist Martin King who built a sea ice simulator in a forest. They asked "How does data become data, where exactly is the field, what practices of maintenance and care does simulation require?"

Kati shared her practice of working with situated questions, intuitive methods, engaged art and science. We discussed extraction and abstraction, collaborations across the sciences and with indigenous populations (human and otherwise). We mused on the benefits and difficulties of infusing "facts" and "data" (such as the levels of underwater noise pollution in the Baltic Sea) with poetic imagination.

The evening was reserved for a very Finnish form of sharing. The sauna. Wood fire, smoke, steam, beer and sausages. Meandering conversations, limited amounts of alcohol with copious amount of twilight.

Fieldwork

Landing is not something that can be learned from books or modelled in a lab. It is an action that connects the person who is landing with the place in/on which you're landing. A moment of reciprocal influence. Resonant, resistant, welcoming, oppressive or indifferent. Only through direct engagement with the place can you be sure where and how you land. With attention and curiosity, you can gradually deepen your understanding of the place. Fieldtrips, learning journeys and site visits are different forms of situated, experiential learning. Learning directly from the locals who are invested in and committed to their specific situation. Their knowledge is grounded in first hand experience with the land. In fieldwork abstract data about the situation gains another dimension. It "lands" in your tangible experience of the world and embeds itself in your bodily memory.

A significant part of the scientific work on Seili happens in the field. We accompanied Jasmin on her daily trip to a meadow where she collects data for a time series on botanical diversity. We began to recognise and record a few species of plants. Equipped with macro and zoom lenses, the eco-artistic paparazzi soon surrounded a rare fern unfurling less than a centimetre above ground. We talked about fieldwork and species identification. About the need for generalists in arts and science. As we talked, Jasmin lead us to a "tick hotspot". We watched as several ticks climbed to the tips of grass blades. Waving their tiny legs in wait for something warm, mobile and bloody to brush against their tiny habitat. Only the briefest of contact is required for a tick to latch onto hair or skin or clothing. Ticks are blind. They don't move much on their own except vertically, until they reach a host. The host provides them with both blood and transport. The host allows them to move into the next stage of their life. From larvae, to nymph to adult. A fellow earthling with an urge to live at any cost, latching onto our "unconditional hospitality".

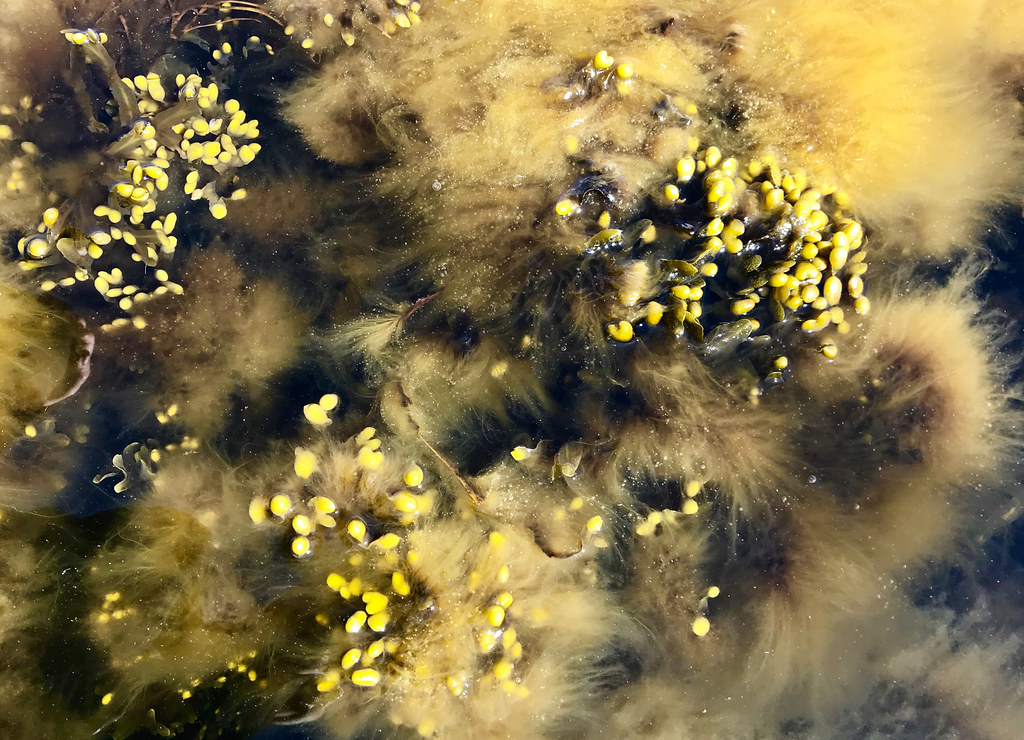

In the afternoon we boarded a research boat for a short trip to a nearby island. We listened underwater to an eerie stillness, only occasionally pierced by signalling of nearby seals. Jari and Katja invited us to join them in rowing, throwing and pulling nets. In exchange they teach us to identify some of the marine life in the coastal waters. The omnipresent bladderwrack, several crustaceans, moluscs and an occasional small fish. We learnt of the relationships between zooplankton and herring in the Baltic Sea, how the changes in sea temperature and salinity affect wider changes. Changes likely resulting in smaller fish, with lower reproductive capacity. While fieldwork is essential, most of Katja's work is statistical. Her foremost tool is a giant, carefully assembled spreadsheet containing decades old time series, with notes on sample collection and changes in techniques. We assume sonifying some of the data could provide new insight. Assumptions require testing. Further research required.

We spent the last evening of the retreat deep in conversation at Jari's home. Cheering the catch of the first 23 herring in the institute's new nets while analysing, perhaps too closely, the failure of CIA'sacoustic kitty. We discussed FoAM's history and collective hopes for future collaborations. Our hosts reflected on why they found it interesting to involve artists in a scientific research institute. Because we ask different (sometimes baffling) questions and can challenge researchers to explain their work from different perspectives. Because we see the situation with fresh eyes. Because we appreciate strange things. Because we provide an opportunity (or an excuse) for scientists to experience familiar places with new people. And with our work, we might be able to lure people into a deeper appreciation of the science and situation of the island.

Communing

Landing can become embodied in sensation by paying attention to the points of contact between your physical body and the body of the land. Landing becomes a form of "communing" with the land and its inhabitants with whom you may, or may not share a common language. It recognises the agency of the place, no matter how incomprehensible it might seem. Communing is a practice stretching across millennia through rituals that thread together a common humanity. Some rituals are a way of asking permission to land. Others focus on greeting, acknowledgement and appreciation. Some provide a way of noticing what the land wants to share, where it wants you to be and what it invites you to do. Alongside rituals, techniques for landing can be found in meditative practices, deep listening, performance (e.g. music, dance, body weather), exercises in practical magic (e.g. scrying, geomancy, energetic navigation), or even simply walking. Landing is can be something you do over and over again, whenever your feet leave and return to the ground. Try landing with intent, try noticing what happens in the moments your body touches the Earth.

Sense and sensing are forms of divination, of prediction. Augury may be defined as the practice of interpreting omens from the observed flight or dance of non-humans, tracked by GPS or satellite; divining both the past and the future, not any present but sheer persistence which is beyond appearance, offering either transcendent meaning or only the earth —Martin Howse

Before departure, Saara sent us out for a "landing" walk. Using our bodies as antennae, we explored the island in various modes for an hour. Noticing the things that went unnoticed while we engaged in conversations with other humans. Wondering how the land was speaking to us and how our mind was interpreting signs. We conducted small observances to greet a new growth of moss, or a vista of particular significance. Listening to the rhythms and voices coexisting on the island at the same moment. Considering different temporalities. Until the return to scheduled time was introduced by the ferry timetable marking an end to the retreat.

While the others embarked with the ferry, the two of us stayed behind. As the ship disappeared into the archepelago, departing from view, we crossed another threshold. Time to reset. To land again and arrive again where we already were.

Attuning

Conscious landing is closely related to practice of attunement. Even if you've been in a place for a while, sometimes experience gets out of sync with the surroundings. You might physically occupy a space while your mind is elsewhere. You can easily overlook the more ephemeral signals continuously emanating from a place, the temperature, the pressure of the wind, the colour of the light, the textures peculiar to a season. Attuning provides a way to (re)connect with your sensory experience. To be touched by a felt sense of place. To notice subtle resonances and disturbances emerging. To more directly engage with an environment.

After days of immersion in the human endeavours on the island, we took some time to explore its less human aspects in silence and solitude. We kept returning to the same places, gradually attuning to the rhythms of the land and the sea.

We approached our residency on Seili in the spirit of Ampére’s “tâtonnement”, or “feeling around”. When exploring electromagnetism, Ampére found that "The necessity of changing methods is all the more obvious when it is a question of finding the explanation of a phenomenon that nature offers in all of its complication. There, where the givens are by their very existence more complicated than the results we seek, direct synthesis becomes inapplicable, and it is necessary to take recourse either to direct analysis if possible, or to indirect synthesis, to feeling around (tâtonnement) and explanatory hypotheses."

We landed on Seili with the intention of becoming more familiar with the phenomena on the island. We came to explore its environmental and social processes, to observe their implications without immediately confirming or rejecting any hypotheses. In stillness and motion, we observed the porousness between inner sensations and external influences. Between our biology and technology. Between studies, stories and experiences. Aware of the effects the environment was having on us and vice-versa. We attuned to the island at various speeds — sitting or lying still, hiking, climbing, walking, meandering, always attentive to the many dimensions of sensory experience.

We listened to the island and its inhabitants. The longer we listened, the more intricate details of Seili's soundscape emerged. Tiny fluctuations in the melody or pitch of birdsong in different parts of the island or different times of the day. The many different sounds of flight. From the low frequencies of swans' laboured take-off, to the busy fluttering of songbirds, the buzz of insects and the percussive compositions of flocks of geese. At night, the hushed atmosphere was occasionally interrupted by loud calls or discordant rustling of the nocturnal animals — moths, dogs, deer, badgers. A polyphony of rhythms and overlapping sounds. The quieting after sunset never becoming completely still. The hum of human activity always present as background radiation. Motorised boats of all sizes, fridges and heaters, aeroplanes and quad bikes, drones and transport carts, The Eurovision Song Contest and Saturday night techno.

We sat on rocks and walked through forests, watching the interplay of sunlight and clouds of swarming midges. At dawn and dusk, light and colour drift in slow transitions. The long hours of daylight coaxed out the viridian green of spring growth. Even the minuscule cracks between the rocks sprouted green. The foliage and flowering plants became more lush with every sunrise. Meadows changed colour as different flowers began to bloom. Gradients of blues, purples, yellows and whites. Moss and lichen drying. Brittle, greying and subdued in the unseasonal drought. Over time, the island has become more prominently dissected between public areas and private property. The space for science and space for leisure. Summer houses and private jetties. The "hordes" of tourists seemed at odds with the scientists' concern for (relatively) controlled ecological experiments.

The scents of the island changed over the week from the bitter green herbs of early spring, to pollen-heavy, sweet smells of flowering trees and bushes. Yet the base notes of specific habitats remained. On the south of the island, the scent of the hazel forest was fresh, musky and herbaceous, while the pine forest of the north was more resinous and dry. The coast smelled swampy, decaying plant matter with a salty tinge of brackish water. The middle of the island was mostly scented by humans. Dust and compost mixed with the floral notes of ornamental shrubs, entwined with smoke and the heavy smell of cooking.

We sought out food that could be foraged on the island to enhance our meals. The abundant viking leak (allium schorodoprasum) and wild chives (allium schoenoprasum) became prominent in our savoury dishes. Pine tips, nettles, wood sorrel, ramson and dandelion tantalised the pallate with their bitter, tangy and pungent flavours. We created new recipes each day, spurred on by our otherwise frugal food supplies. Wild allium and oat cream risotto, Sauteed pine tips with the Finnish grilled cheese, Porridge with cowslip and strawberry coulis, the fresh taste of Wood sorrel lemonade.

It might seem indulgent or pointless to spend time attuning to an environment when circumstances demand urgent change. Yet taking time to attune to the effects of environmental turbulence can motivate more engaged action, an intimate connection to a place can provide more suitable methods and lasting results. Well meaning, but inappropriate action can sometimes be more detrimental than doing nothing. In some cases, when "fixing" something becomes impossible, a palliative "being with" a changing landscape can be the most appropriate act of care. In other cases, caring requires immediate and direct action (e.g. preventing the clear-cutting of a forest). Discerning how to be and what to do in an environment when we're visitors requires careful protocols of engagement. From understanding the gradient of consumption (i.e. how much can we eat without causing harm), to negotiating the various give-and-take. Gaining permission or invitation takes time when no explicit communication or consent is possible. We may need new rituals to re-familiarise ourselves with being in other-than-human contexts. Times, places, feasts or talismans to focus intent, to evoke and invoke the spirit of reciprocal relationships with the island (for example) and the wider archipelago.

Sensing beyond human scale

Once upon a time, not so long ago, landing in one place was a part of becoming disconnected from other places. This can not always be assumed any more. When you land somewhere, you can usually remain tethered to the rest of the world through digital devices. Even in a place with intermittent network connection, the devices land with you. They can direct your orientation and guide you through unfamiliar territories. They can help you land and navigate. They can connect and communicate with other devices in the area. They can mediate, capture, filter and distribute experiences of the place, long after you're gone. Landing in the 21st century is inevitably a technologically enhanced practice.

To hear the smaller, quieter voices of the island we resorted a technological augmentation of our senses. We could pick-up a range of vibrations through the air, rocks, or ant-hills. Yet, the biological and geological scales that drew our curiosity remained mute to human ears. With the help of microphones and digital sensors, we began to hear unseen life in the undergrowth, between reeds and in the trees. Our instruments let us to listen to the island across wider spatial and temporal scales.

Humboldt's instruments were not understood as transparent means of registering nature “in itself". [They] were the concrete media occupying the milieu, the “halfway-place” between the mind and the world: the concrete locus for the fusion of sense and intellect. Humboldt's instruments not only extended his senses, heightening his perceptual faculties and submitting sensory phenomena to mathematical scaling; they were embodiments of his relations with others and his place in the natural and social world. The well-tempered instrument, like a reliable but spontaneous human, oscillated within a specific range of values, passive in receiving, active in transmitting its phenomena. —John Tresch

Fast-forward a few hundred years. The boundaries between transmission and reception, passive and active have long since blurred. Our instruments have developed by leaps and bounds, yet the complex interactions between humans, their instruments and the world have not always "extended" or provided a "heightening". What if we focused as much attention to our own attunement with the world as to tuning and tweaking our technological devices? What technologies could help us attune to our surroundings, instead of drawing us away from them?

We are interested in minimally intrusive technologies able to enhance or remind, rather than distract from an environment. Technologies that can augment our sense of immersion in a particular environment. Technologies capable of altering or augmenting the spectrum of human perception. Aural interfaces, wearable technologies, high resolution translucent HUDs. No cables, no buttons, no screens.

We imagined designing a sonic lab where we would listen to different lifeforms on the island, through time-folded field recordings and sonified data. Or perhaps a sensory deprivation chamber where we could listen to the sound of "post glacial rebound". A soundwalk welcoming visitors to the multispecies habitat of Seili. We could imagine ambient overlays to offer alternative readings of the landscape, challenging preconceptions of geopolitical boundaries (e.g. the native land app, indigenous and transient forms of mapping). Sonic filters to modulate experience using local environmental data (eg. Sonic Kayaks).

We are curious about technologies — digital, chemical, biological, or philosophical — that can help focus (or maintain) our attention on the experience of "landing" in different ways. Technologies to "feel around" climate models and time series. Speculative technologies through which we can explore possible, probable and preferred futures of the island, on the island.

"The group considered the way that sensing the environment, with the body and with instruments, could open the potential of divination as an aesthetic practice to reveal meanings and even derive potential and information from objects, organisms, and states of change in the natural world. Divination, for these practitioners, seemed to be defined in opposition to understandings of the environment that might be constructed as shared or even universal, as in the case of the scientific use of technical instrumentation or data-driven interpretation of organisms or environments. Instead, divinations in this context denote a radical subjectivity such that an individual’s personal experience—for example, an interpretation of signs from animals or the weather—is taken to be meaningful." –Hannah Star Rogers

Departure

One last walk, looping around the small island. A ritual of un-landing, of de-parting, of em-barking, of leaving. Suffused with a different kind of appreciation and gratitude. A melancholy of separation. Acknowledging that we are merely passers by. Guests for some, food or even a nuisance for others. Aware that our presence can only be temporary. We come and go. Our work might appear, perhaps linger as a faint trace of memory, and eventually disappear. Landing and leaving deliberately engages with impermanence. The impermanence of our own lives and the impermanence of aeons on geological or cosmic scales. At times humbling, terrifying and liberating, impermanence as the essence of spectres in change.

“No species is permanent.” Karl Schroeder reminds us “Only the ecological niches, the environments friendly to one or another kind of life, have any kind of permanence. They saw that they would rise and fall like every living form. So, instead of trying to extend their existence, like so many other species before and since, they looked to ways of preserving and nourishing an environment that would encourage the birth and growth of species similar to themselves. Nothing's permanent. But everything can hand what's unique, what's best about itself, to what comes after."

* The island, not the asteroid 2292 Seili (1942 RM)

Created: 15 Jul 2021 / Updated: 18 Aug 2023