Accesslab Pilot 1 Notes

Posted May 31, 2017 by Amber GriffithsLast week we trialled a new type of workshop aimed at improving access to scientific research. We are inspired by Science Shops, where anyone can pose questions, and be partnered with university researchers who help to answer them.

Our aim, in collaboration with the British Science Association, is to design a workshop model that performs the same role as a Science Shop but requires no infrastructure and little funding. We are aiming to develop a model that can be rolled out to diverse audiences.

We began with a pilot funded by FEAST Cornwall to partner science researchers with artists.The workshops were designed to test some potential approaches, assess the level to pitch future workshops, and to develop the content that needs to be included.

We were joined by Dr. Katherine Smith from the University of Edinburgh, who specialises on Social Policy. Kat came to both sessions, talked to all the participants, and gave us extensive feedback. This non-invested outside perspective was extremely valuable.

Below is a detailed account of the pilot workshops, in roughly chronological order, together with some analysis of the results that came from various tasks. Most of the science participants were biologists or medics, while the arts participants included a film maker, dancer, composer, ecological artist, choreographer, designer, community artists and chef. We began with a preparatory evening workshop just for the science participants, then ran the main workshop with the ten science participants and ten arts participants.

At the end of this rather lengthy post are some points for how we would change the workshop in future.

Preparatory evening workshop

Information challenge 1 – an individual perspective.

We asked participants what sources of information they used to decide how to vote in the UK referendum on EU membership. They wrote down each source on a single small piece of paper. We then asked them to place those sources along a ‘corridor of trust’, ranging from sources that they thought were very untrustworthy (‘Glorious Hoax’) to those that they trusted a great deal (‘Reputable Sincerity).

Predominant sources of information listed by the participants were various mass media/news outlets (15), friends/family/colleagues (10), and social media (7). A small number sourced information from academic experts (4) or directly from what politicians had said in parliament or local government (3). Other sources listed once each were EU signs on buildings, the Office for National Statistics, ‘books’, ‘historical perspective’ and ‘opposing voices’. Friends, family and colleague sources were spread along the whole trustworthiness scale, social media sources tended to be closer to the Glorous Hoax end, mass media mostly clustered around the middle, and expert sources were at the Reputable Sincerity end.

This task highlighted that when you are a not a specialist in a field, you are likely to rely on the most common and easily available channels of information rather than seeking out specialist literature. It also shows that people seek information from sources that they know they don’t trust. The purpose was to ensure that the scientist participants could see that this is normal and OK, and to encourage them not to think that others are mistaken for taking the same approach when seeking science information.

Introductory talk.

We covered some basics of why people might benefit from access to research – for example patients making decisions about medication, parents deciding whether to vaccinate their children, fishers choosing which species to harvest and how, and politicians designing climate change policies. We talked about artists in the same context – as their work is often inspired by real-world problems and events – if the information foundations are shaky, the artistic work may not be as effective as it could be.

We touched on some of the problems that can come up with science communication – particularly that when people get upset by a scientific finding, it is usually because it is encroaching on a deeply held personal or cultural core value. We talked about how people are sometimes right not to trust science, covering issues like scientific fraud, dubious funding sources, ethical problems, and real/perceived arrogance of scientists. The aim was to prepare the scientist participants to be open, thoughtful and listening when working with non-specialists.

Information challenge 2 – for the big problems.

We asked participants to note down on paper what they thought the most pressing issue of our time is. We gathered these up and sorted them into five categories – climate change impacts, energy futures, ageing population, antimicrobial resistance, and inequality. We split the group into pairs and allocated one topic to each, then asked them to find the three most important peer-reviewed publications on those topics – the papers that they would want policy makers to read. Each pair made a poster with the topic and the three papers listed.

We then took the posters away, and while the workshop continued, we searched for each paper. Any papers that could not be accessed because they were behind a paywall were stamped with a red dollar.

At the end of the workshop we brought the posters back, showing that 7/15 of the sources that the scientists wanted policy makers to read were paywalled. The purpose was to highlight how serious the issue of accessibility of research findings can be.

Snacks were provided by Hoon Kim to inspire and awaken the participants.

Group task – finding information and judging sources.

We split the group in two, tasking one with noting ways that people could access scientific research, and the other with noting how the quality/reliability of a piece of research can be judged. We went through each item as a group, voting on how many people agreed or not with. The higher the number, the more useful each was deemed.

Together we talked about how some ways of judging quality of papers are more suitable than others for a workshop with people with no research background – for example most people should be able to work out if a funder might result in a conflict of interest, but assessing the methodology requires much more training.

The most popular routes for finding papers were Google Scholar and Wikipedia – some newer methods like Unpaywall and Sci-Hub were voted lower, but on discussion this was because people hadn’t heard of them. Participants were encouraged to look into methods that they hadn’t come across before as preparation for the main workshop.

Preparing research devices.

Scientist participants were asked to shut down any VPN links or log-ins to university libraries, and to check their access by trying to read a particular paywalled paper. This was to prepare for the main workshop as the scientists would be working in pairs with artists, and we wanted them to be able to research with the same level of access to papers.

Main workshop

Challenge 1 – where do you seek information?

On arriving at the workshop, we mock-diagnosed all participants with leprosy. This disease was chosen because it is unlikely any of them would have had it, or know a great deal about it. We asked them to write each source of information they would look to on a separate piece of paper, and place these along a scale of trust.

The purpose was to highlight the stark differences in where people seek information. Science participants routinely sought academic literature, were more likely to talk to friends/family who were in the medical profession, and more likely to look to international expert organisations like the World Health Organisation – these sources tended to be placed highly on the trust scale. Arts participants rarely mentioned these sources, and listed more diverse sources like historians and theologians, which tended to be placed lower on the trust scale. Science participants used 50% more sources of information than the arts participants.

It would be valuable to continue to collect this data in future workshops – once enough has been gathered it may make for interesting research in its own right.

Introductory talk.

Here we focused on what scientific literature is, what it can be useful for, and a brief foray into the history of scientific publishing to explain how we got to a situation where so much research is published but so little is openly accessible.

Challenge 2 – Basics of scientific research.

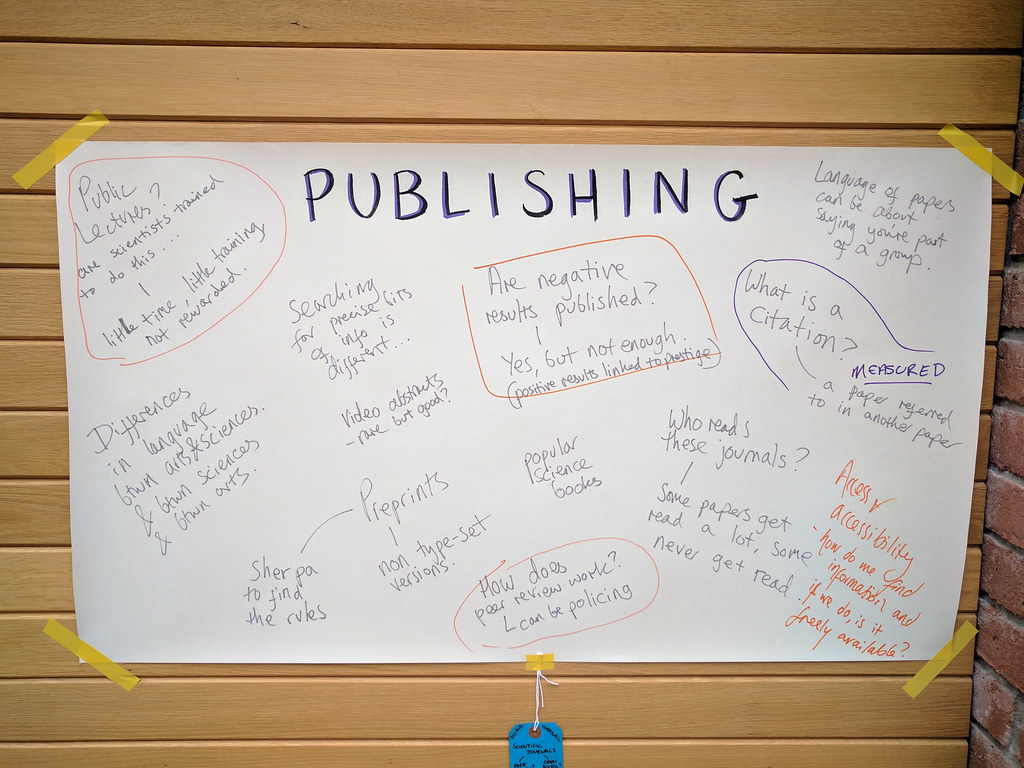

To develop the ideas from the introductory talk further, we split the group into three, with each group made up of a mix of backgrounds and career stages. Each group spent a short time discussing how scientific research is funded, how it is published, and how non-specialists can tell if a piece of research is good quality. We picked these three topics to cover the most basic information that someone would need to know to make use of scientific research. One artist participant from each group then pulled out the main points to tell the whole group.

The purpose was to hone down what information was deemed most useful and interesting – in this way we can design future workshops with better focus and pitch. A number of interesting moments happened within groups – in the Judging Quality group, an artist participant mentioned that they look for whether something is well formatted and aesthetically appealing as an indication of the effort that has gone in and as a proxy for quality. The scientist participants were initially highly sceptical but later realised that they do the same – judging the reliability of graphs based on how they look and which package they were made in for example.

Talk – How research ends up in the news.

We took a case study of a media article about some scientific research, and explained how that research ended up in a newspaper – including who writes press releases and how these reach the journalists. We then went through some simple ways to check whether science that we read in the media is reliable: (I) Can you find the original research? (ii) Who did the research? (iii) Who funded the research? (iv) How was the work done? (v) Did they actually do what they say they did? (vi) What else have others published? (vii) Can you access the data?

Lunch was provided by Hoon, who joined us as a participant for the rest of the workshop.

Research in pairs.

The participants were given time to do research in pairs, with one artist and one scientist partnered based loosely on interests. Before the workshops we asked the artists what topic they were interested in doing research on – these included climate change, cryptocurrencies, injury, human behaviour and so on. A fortnight before the workshops we asked the artists to hone down their ideas to more specific questions in preparation for this session.

The scientist participants were briefed to not provide subject specific information, but simply to do research together – allowing each person to see how the other goes about research and what sources they might use, learning from each other.

It was tricky to judge how long to make this session – we settled on 1.5 hours, but most pairs continued into the break after – so two hours may be better in future.

Evaluation.

We asked participants what was new for them in the workshop. One comment that stood out was that an artist participant felt he was teaching his computer a whole new language – the search terms he was using were very different from how he would usually look for information. A few of the scientist participants expressed shock at how difficult it was to do research without the access to paywalled journals – they had been aware of the problem in theory, but not known how bad the situation was.

At the start of the day we asked participants to place a magnet on a scale showing their level of knowledge vs. confidence at (i) talking with non-specialists about their own work, and (ii) doing research on a scientific topic. At the end we asked them if they wanted to move the magnets. This approach is flawed as we got a group clustering effect where people were strongly influenced by each other, and many did not move their magnets, however the results are shown below. Artist participants are those with black symbols, and scientist participants have orange symbols – each person drew the same symbol on their two magnets so we could follow the data anonymously:

We asked participants to write down any new sources of information that they would now use – both scientists and artists appeared to broaden their sources:

Finally, participants wrote down anything that they found useful/interesting, boring/excessive, or missing/wanted. These have directly informed the section below on things to change, but here are some direct quotes of things people liked:

‘Celebrating the diversity of knowledge’

‘Really really useful to know that scientists do see a value in working with artists and don’t always find it frustrating and contradictory’

‘Interesting to find out about the structures and hierarchies of scientific research’

‘Having the one-to-one pairing with a scientist was an amazing opportunity’

‘I learned about ways and methodologies of searching for information and articles. Having these research processes explained on a 1:1 level, in the context of my own arts research, was very valuable’

‘Re-considering the politics of knowledge and challenging it’

‘Further appreciation of multi-disciplinarity via this experience’

‘Was beneficial as a scientist to do similar activities on the preliminary and full workshops to really see the differences in scientist/artist perspectives – helps us to be more aware!’

‘Provided me with a fresh perspective of my own work and why I do it – realising the wider applications of my research outside academia has inspired me’

Things to change:

We need to include a case study of how research ends up as a publication, covering how the researcher gets funding, how they get paid, how long the research takes, what a journal is, how they choose a journal, and how the peer review and editorial processes work. As part of this we can talk about the moves within the scientific community towards new models for improving academic research and publishing. We could begin this case study by searching for a topic, and showing the sheer volume of papers that are out there. This will be particularly important for audiences who are less familiar with the concepts of research than the artists were. [inspired by feedback from Charlotte Brand]

If in future we use a board to measure participants’ confidence and knowledge of doing scientific research, we need to avoid the group clustering effect by asking people to privately write a number down for each and to hand that to us – then we can place them on the scale ourselves without them being influenced by each other. We can repeat this at the start and the end, and then analyse the results after.

We need to keep the numbers lower. In this workshop we had 26 people, including 20 participants. Smaller groups of ~16 are much more relaxed and easier to manage. With a smaller group an introductory round becomes feasible. One participant mentioned problems hearing, which could also be improved by having a smaller group.

We need to find a way to reduce scientists' tendencies to slip too much into a teaching role.

We need to be clear with participants that their research time is just for them, and we don’t need to know anything about what they are researching.

The majority of our science participants were PhD or postdoc - which may reflect changing attitudes to the importance of this sort of work. We should think about whether/how to encourage more senior researchers to get involved.

Many people commented on how good the venue, materials and food were – this is something to continue to place great effort on. It may be worth highlighting in any materials we produce that coming to a relatively neutral location is key for workshops where different societal groups are brought together.

Several participants said that they spent much of the research time honing the questions instead of finding information. This seems just as valuable a use of time, as it is a core part of doing research. Several people put in their feedback that they wanted the co-research session to be longer. In future, we could explicitly split the time so that they have 30 minutes to hone the questions, and 90 minutes to do research. The artist participants were asked to hone questions before the workshop, but there is clearly great value in doing this together with a scientist.

Those who hadn't sat next to each other in earlier parts of the workshop spent a fair amount of their research time getting to know each other. We could extend the research time and also make sure that pairs are not sat together earlier in the day, to encourage more people to meet.

For lunch, one of the dishes was shared between two, and few people took from these shared dishes – possibly because they didn’t know each other well. Next time, we may build in the sharing of food into the research pairings – introducing the pairs to each other beforehand, then having lunch together, then doing the research together.

The whole budget for the pilot workshops was £1k, which covered catering and people’s travel but no paid time for FoAM staff to develop or run the workshops. We now need to secure adequate funding to run these develop these workshops further, in a sustainable way. We would like to develop workshop materials for others to be able to roll out the model, and an information pack on how to find and use scientific research for non-specialists.

Some participants wanted more prior information on who they would be paired with – the pairings took a surprising amount of time to arrange, with several cancellations and replacements, making this tricky to do. When we run our next trial we will keep this in mind, and make a decision at that point as to whether this is feasible. One participant commented that knowing the pairs in advance might be restrictive.

The case study taking a media article and finding the original research seemed very successful - we could also run a paired task based on taking the same approach as practice before the main research session. For example, participants could bring an article they have read that they want to fact-check.

One person criticised the materials as being non-recyclable – however almost all materials were re-used from previous projects, and will undoubtedly be re-used again. The magnets were re-used from this project. But - we do need to think about what materials people will need to run these workshops themselves, so that we can provide recommendations that are recyclable and sustainable. Magnets will not be suitable for a national roll-out!

There was some misunderstanding about the purpose of the workshop - we are designing a model that could roll out so any identifiable group can be paired with scientific researchers. The choice of artists as a first test group was a case of form-following-funding, as our funders were a local arts organisation who liked the model and wanted to support it if we were willing to try it first with artists. The next trial, run by the British Science Association, will be parents working with immunologists. We built in ways that the artists’ opinions and experiences naturally fed into the workshop as a whole, and many participants commented on how they felt it was a two-way learning process. If we are designing a model suitable for a roll out to broader audiences, the big challenge is how a more two-way process could consistently work regardless of those involved. Perhaps an exercise focusing on how each group assesses quality of information could help here - this could very easily follow on from the exercise on what sources of information people use. This deserves more thought...

Created: 15 Jul 2021 / Updated: 15 Jul 2021